(This is an archived old post from the previous version of the page.)

How can a game have issues and still be one the best gaming experiences ever? Welcome to SOMA.

Thomas Grip, Creative Director at Frictional Games (Amnesia, SOMA), is a man very passionate about games as a story-telling medium. So am I, and my online dialogue with Thomas resulted in creating (Thomas did most of the hard work) a narrative frame design we called the 4-Layers. We both used the frame during the design phase of our games.

Considering that our findings are not quite compatible with what a lot of other designers and studios do with the story-telling in their games, you can imagine how excited I was to see the attempt to execute the 4-Layers in someone else’s creation.

Like a few other game designers, a year ago I did play SOMA alpha to provide early feedback to Frictional, but it was not a full game and obviously the final version is where it’s at anyway.

After finishing SOMA, I can tell you this. Frictional have created an incredible game, one that gets better with each hour until the breath-taking finale. But they also made a game that confirms my suspicion – one I developed after Ethan Carter – that our idea of how to make a perfect narrative game is:

a) correct, and:

b) unsustainable in the real world of game development.

It is a blind alley, a cul-de-sac, a dead end street.

Unless…

But I will get to that later. First, let’s talk about what SOMA did right.

Whatever critique you read here, make no mistake: SOMA is worth every penny, and it’s an unforgettable experience. If I wanted to go authoritarian for a second, I would say it’s a game that every self-respecting gamer should have in their library.

The game enjoys 91% positive user rating on Steam, and gaming websites will tell you that “SOMA surpassed my expectations of what a psychological science-fiction horror story could be” and “SOMA is one of those once-in-a-generation experiences that so wildly defies both expectation and assumptions that I can say with confidence that it will forever impact how we define video games.”

It’s all true.

I don’t think there’s any point repeating all the praise here in this particular blog post. But if you have even harsh critics and not exactly fans of explorers like Jim Sterling say “Despite being predominantly a survival horror game, [SOMA] embarrasses most high profile narrative-driven exploration games with its reflective, evocative exposition and quiet, brooding atmosphere.”, then you know you are in the presence of a game of the highest caliber.

SOMA imprinted a few unforgettable memories onto my brain. It’s one of the moodiest games ever created, fearless in its execution of darkness and decay. It features the best audio since Dead Space. It offers what is to me one of the best puzzles in the history of video games (no spoilers here, but if you played the game, I mean the “scan puzzle”). The monster encounters resulted in a pants accident better left forgotten.

And yes, the story is fantastic, and the game even features a few Telltale-quality moments of difficult choice. Except they are all in-gameplay, if you know what I mean. You will pause. You will hesitate. You will gasp in awe when That Thing Happens But Okay No Spoilers.

So with all that in mind, why do I say the game is a proof that the narrative frame it uses is not sustainable in the real world of game development? Did something go wrong?

It’s not the roughness that we can experience in a couple of places. Yes, the dialogue could have been better, and the voice-overs should have been better. The secondary stories bored me, and the pacing is not ideal. It is annoying that a game in which you find and analyze and sometimes use photos and hand-written notes and computer screens does not have a zoom button.

And so on and so forth, but look, it’s an indie game for $27 made by a core team of fourteen people, not a $59 blockbuster made by a thousand developers. So personally I did not mind this kind of roughness. It did not affect my experience.

And, for what it’s worth, that “roughness” applies only when compared to the best games ever. Objectively, SOMA is one of the most polished and best executed games I played recently, indie or AAA. It sets an impossible standard for most indie developers.

So what exactly is my problem?

If you are interested in a deeper look at the 4-Layers approach I mentioned earlier, read this by Thomas Grip or watch my presentation at Digital Dragons 2014 (4-Layers starts at 36:11). But here’s the super-short version:

Layer 1, Gameplay:

Players must accomplish things through their own mental and manual effort.

Layer 2, Narrative Goal:

Players must understand and agree with short-term goals and objectives.

Layer 3, Narrative Background:

Players’ efforts must unveil more and more of the big picture.

Layer 4, Mental Modelling:

The game needs to provide an awareness/experience filter.

If any of that sounds cryptic, don’t worry about it, or, again, please use the resources I mentioned earlier.

Making a game that properly uses the 4-Layers is a Herculean effort. There is a reason why SOMA took five years to make, and why The Vanishing of Ethan Carter took two instead of the planned one.

On the surface, it all sounds easy. Okay, so if I have a puzzle in the game, it needs to be cohesive, engage the player, the player must understand the context and agree with the action, through their actions learn more about the world, and participate in the experience with certain mental filters in mind (like scanning the environment when you play Slenderman, for example).

In reality, it’s all incredibly hard to execute.

By my biased and subjective estimation, 99% of all puzzles in 99% of all adventure games would not pass the 4-Layers filter. You often solve a puzzle just because there’s a puzzle to be solved. Or you solve it without increasing your knowledge of the world. Or the solution works but makes no sense in the context of the world (e.g. an abstract solution in a realistic crime mystery game). Or the puzzle is fine but the players see easier solutions that the game does not allow them to execute (e.g. players have to pick a padlock even though they have a hammer and a hacksaw in the inventory).

Trust me, as one of the creators of the 4-Layers, I know. The end results can be wonderful, but making a game that is in sync with the 4-Layers is extremely demanding.

I guess it’s no wonder, then, that SOMA often gives up on and violates the 4-Layers.

For example, I did not necessarily agree with a few objectives. I saw better solutions, or I had serious doubts that no one was able to address. So every now and then I just had to “go with the flow”, but I did it mechanically, and only to progress in the game – not because I really wanted to.

Another example would be that sometimes you can do many things in a given situation or a place, but only if you do them in the correct order. Say, read a note first, and then interact with a switch. But if you do it in the “wrong” order, the activity locks you out of the options. Sticking to our example, interacting with the switch would make it impossible to access the note.

I guess it might be fine if there is a good reason for such behavior, e.g. the switch floods the room, but quite often there’s just no reason other than Reason X.

Reason X? Yes, I will decipher that shortly.

Of course, a lot in SOMA is a perfect execution of the 4-Layers, and I love to think that’s part of the reason why people like the game. And, curiously enough, some solutions in SOMA look like they were done incorrectly, but in reality they’re still 100% 4-Layers.

For example, you will often try random things in SOMA. Say, you press a button just because there is a button to press. You do not understand what that activity will accomplish, you just do it.

This looks like something that fails the Layer 2, Narrative Goal. In reality, it does not, because trying random things is exactly what a desperate man would do if he found himself in a place he did not quite understand. Like a futuristic underwater base. So there’s actually a very nice alignment with the core story here.

Anyway, I can honestly tell you from experience that filtering your design through the 4-Layers is an incredibly hard and demanding task. So hard and demanding that after The Vanishing of Ethan Carter I told myself to never do it again. It is something creators do all the time and then after they rest they regret these thoughts, but still, you get the point. Hellishly hard. Hellishly demanding.

But …the main problem that SOMA suffers from is not the occasional violations of the 4-Layers. Its biggest sin – for me, at least – is the lack of the fifth layer, one I would call “Layer 5, No Exceptions”.

Yes, I just blamed a game of lacking a layer I just invented. I also fully agree this layer might just be my own personal obsession, because yes, lately it feels like an obsession.

But, look, whenever a game – SOMA or any other, for that matter – breaks its own rules, my engagement suffers.

I guess it’s the easiest to explain with actual in-game examples, so here we go.

Let’s start with the physics. You can physically interact – move them around, throw them, push them away, etc. – with almost all items and objects in the game. There is no real purpose behind this feature other than simulating the features of the real world, and thus increasing the sense of presence and immersion.

Awesome, right? Right. There are smaller issues with this feature (e.g. it’s often confusing if an item is a decoration or an Important Gameplay Item), but in general, good idea.

But… These items you can interact with:

But these items you cannot interact with:

With these items you can interact:

But with this item you cannot interact:

Ideally, there should be “No Exceptions”. If I can move objects, I should be able to move all objects that look like they could be easily moved. Otherwise I am playing a guessing game with the designers.

Maybe there is a key, like, you cannot interact with items larger that a shoe? No. For example, you can move a chair around, but not a shoe box.

The end result is that a feature that was implemented solely to make the world more believable, was executed in a way that made the world less believable for me.

And what’s the reason for this confusing solution? Reason X, of course.

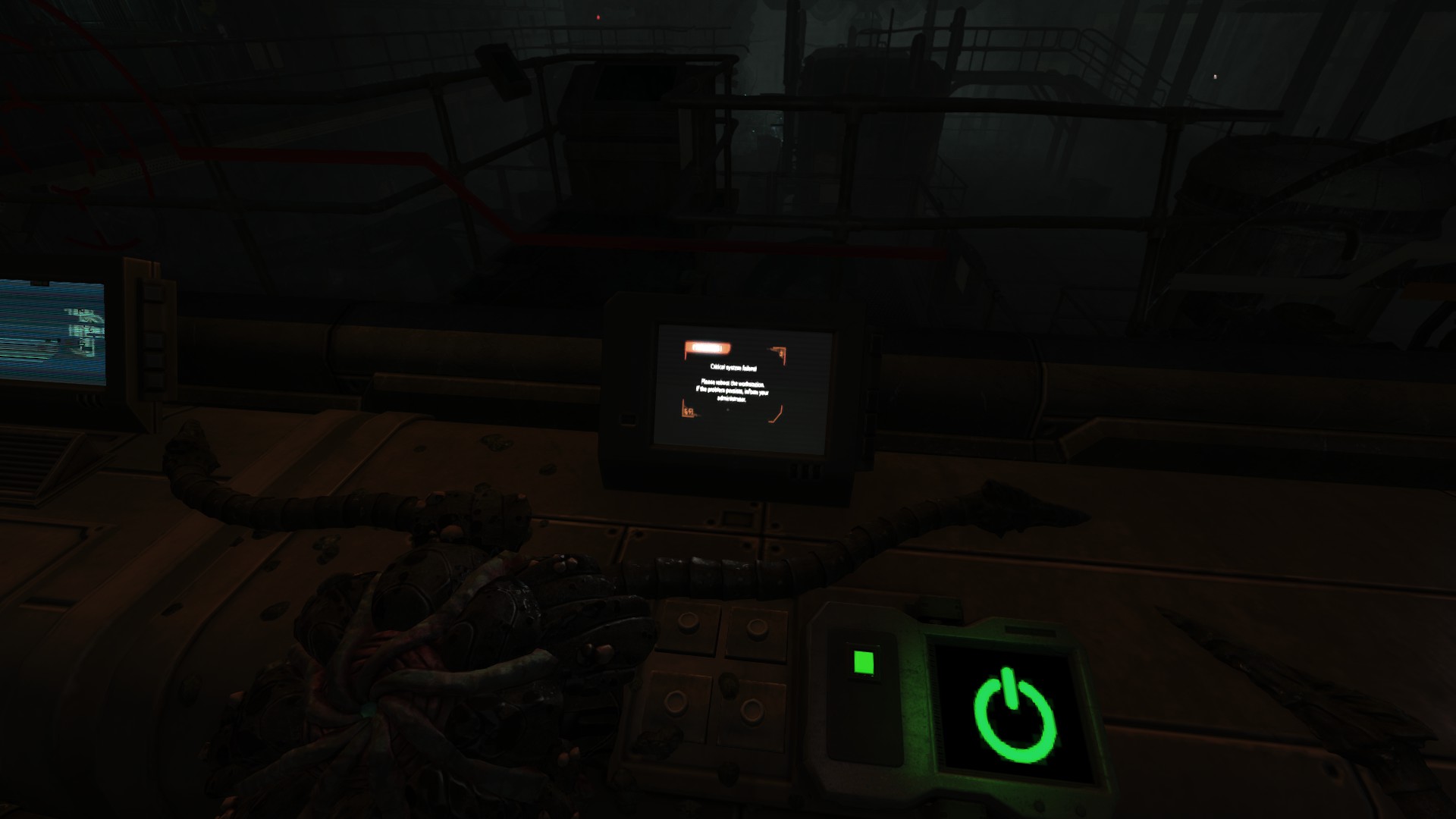

Another example. I have a gizmo called Omnitool.

I can insert the gizmo in special gizmo-reading machinery, but I cannot take the gizmo back until the game allows me to, after doing some puzzles.

Why? Yes, yes, Reason X.

Another example. Sometimes, you can use a ventilation shaft to move around. But all shafts?

No. This one you cannot interact with. The game does not tell you it’s locked or whatever. It’s just a dead element of the decoration.

You might even think that the game distinguishes between interactive shafts and non-interactive ones by making the former partially destroyed but no, this one you also cannot interact with.

Another example. I could plug in this power cord into that computer.

But I could not remove it. And in this particular case, I really wanted to restart the computer to again access the root after the game locked me out of the system’s menu when I interacted with one of the options.

Another example. Why is this note readable?…

…and these notes and that newspaper are not?

Reason X.

Final example, for me especially jarring as this happens in the very beginning of the game.

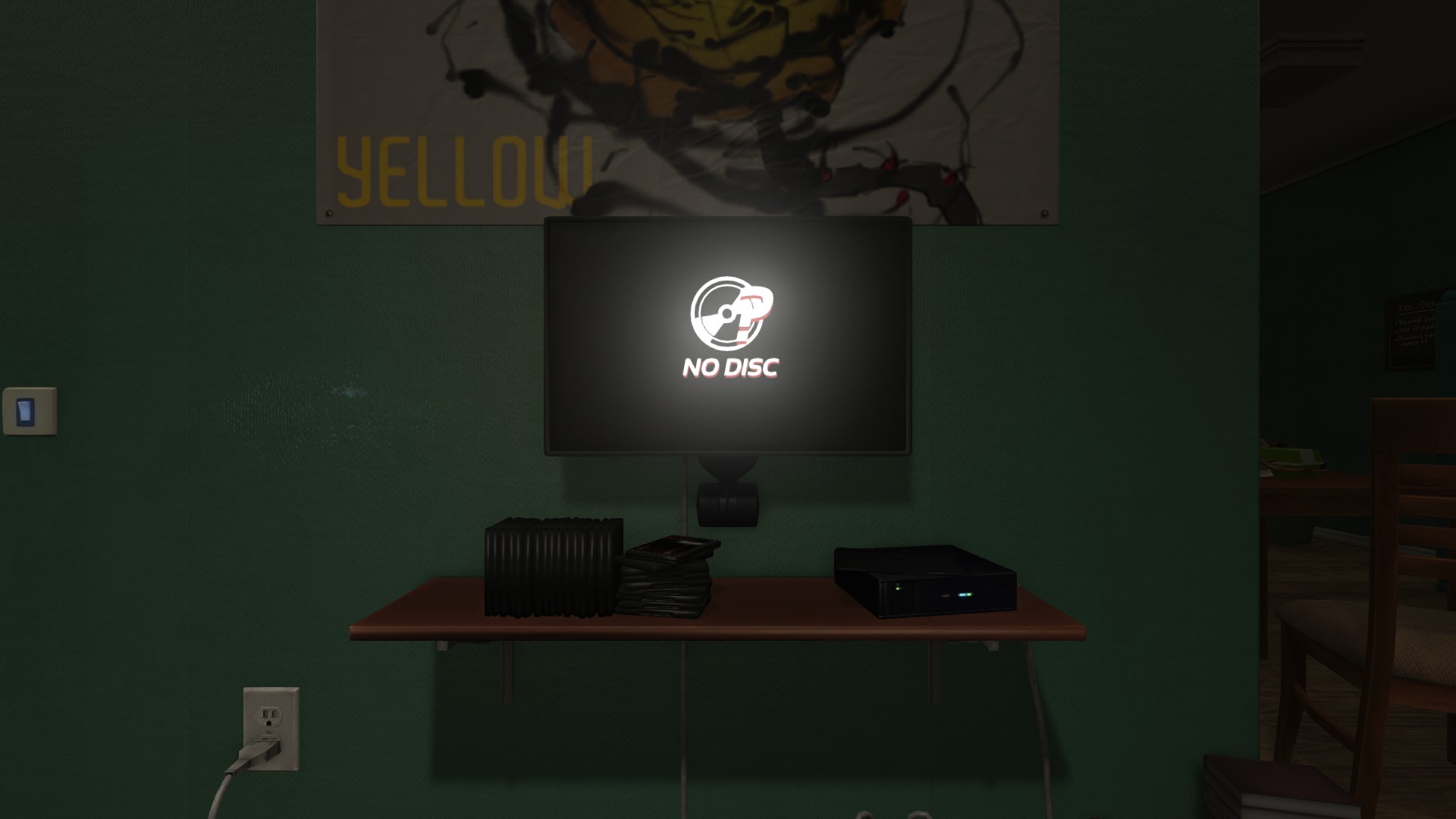

You turn on the TV and DVD player and you see that the disc is missing.

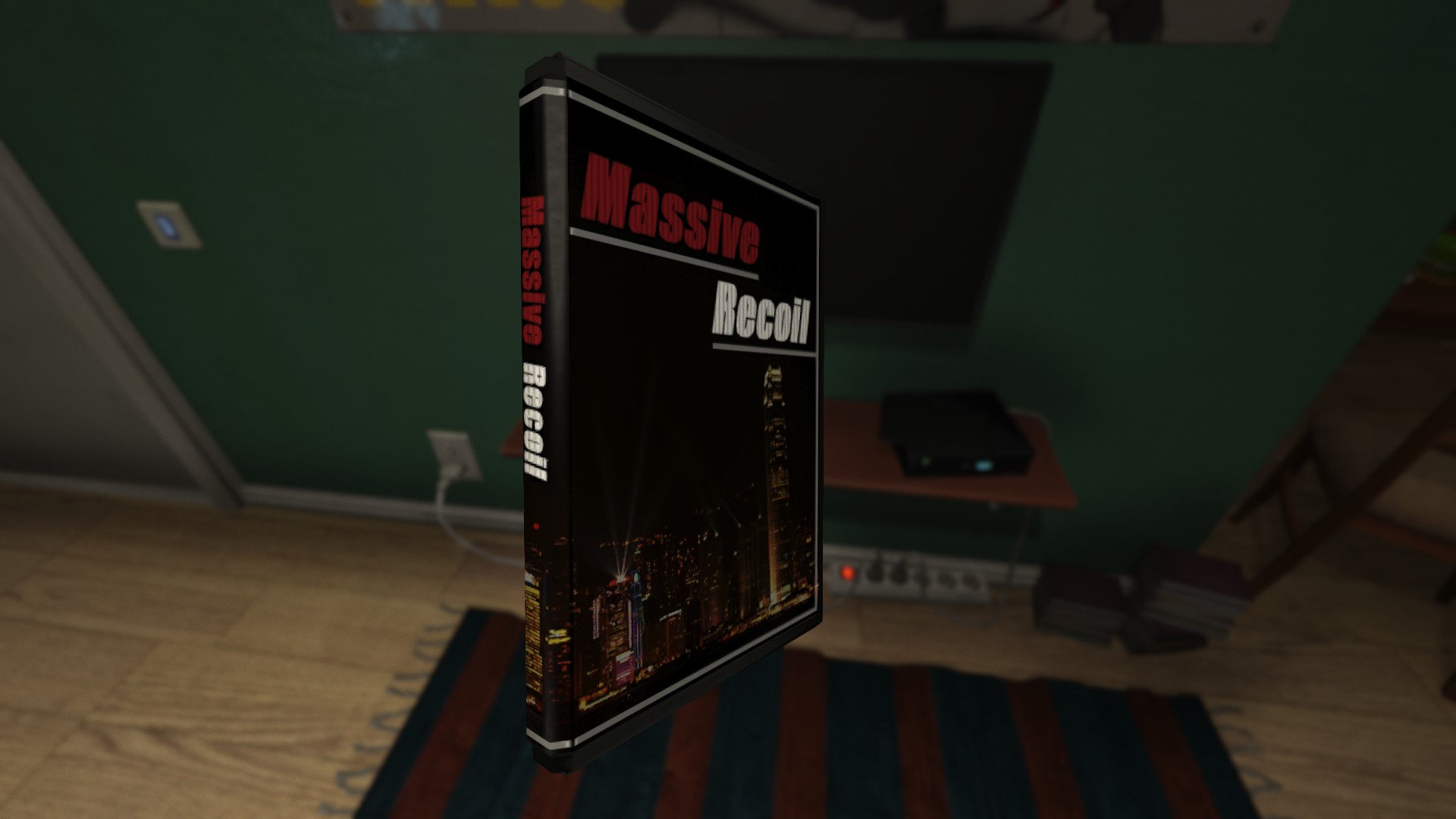

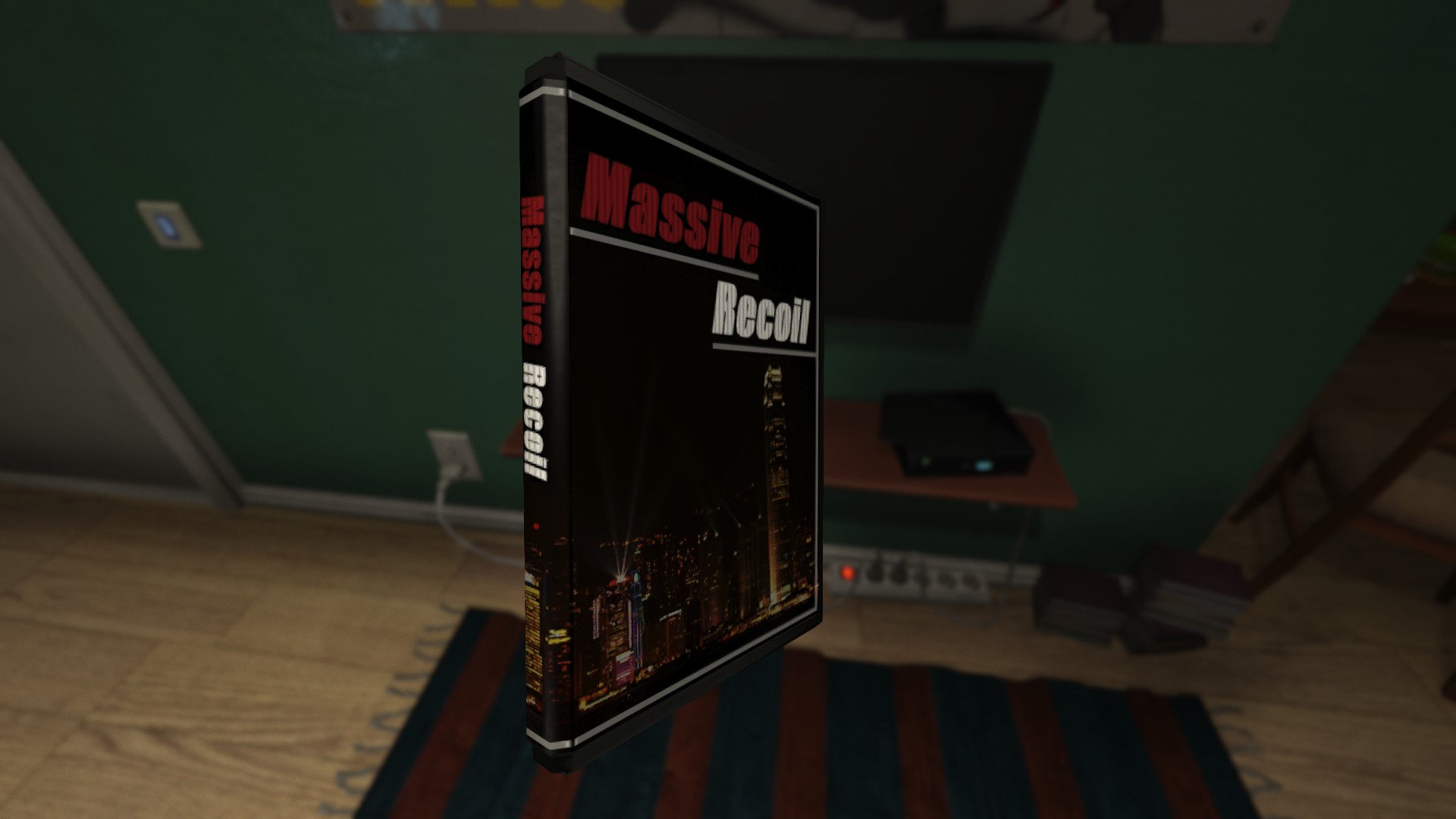

You can pick up a DVD of a movie, examine it, move it around.

But you cannot insert that movie into the DVD player and watch it, or at least see “DVD disc unreadable” message. Even though you do insert things into things later in the game.

Why?

Reason X.

And so it goes with the game. Some computers you can use, some – identically looking – you cannot. Some buttons do things, some – identically looking, and even blinking – do nothing. Some useful looking items you pick up and use, some useful looking items are just background decoration.

But look, I am 100% sure that Frictional developers know all that. They know about all of these issues. I have literally zero doubts about it.

The mysterious Reason X is mundanely simple. It’s time, it’s effort, it’s money.

Adding cohesiveness of interaction to a complex game, but especially to the scripted single-player experience, is a gargantuan task. I know it because just as SOMA violates the 4-Layers and adds the layer of anti-cohesiveness, our own game does all those things as well.

We did fight hard. But we lost that battle. And you cannot open some doors in Ethan Carter even though you find heavy tools you could smash the lock with, and you cannot close wardrobe doors once you open them.

Why? Time, effort, money.

And that’s just simply the act of execution. Actually trying to make the world 100% cohesive and making it all work with the 4-Layers is pure insanity. If designing with the 4-Layers is hard on its own, then with that fifth rule of “No Exceptions” it borders on impossible.

A simple example. Imagine you can use a crowbar to interact with the world. The crowbar is able to destroy a wooden door, for example. The players do it earlier in the game once. (Note: this is important. This blog post is not about demanding a proper simulation of everything! It’s about sticking to the rules a game establishes. If I can turn on the light, I should be able to turn it off.)

Now imagine you want a part of the game to take place in a hotel, room 237, to be exact. In the name of cohesiveness of interaction, you should allow the players to be able to destroy any door in the hotel.

Now imagine modelling and populating every single hotel room with both generic (bed, furniture) and personal (whatever the hotel guests have in their rooms) assets.

Insanity. Building an entire hotel just so on their way to room 237 the players can properly interact with everything is insanity.

And this is exactly why I said it earlier that the 4-Layers, now 5-Layers, is a) correct, and b) unsustainable in the real world of game development.

But I also said “unless”. Unless what?…

1. Unless the players agree to the contract between them and the game in which they promise to ignore some of the issues. I explained it more in detail in my post on Metro: Last Light. However, the game itself needs to make the rules of this contract clear. Otherwise no amount of the good will from the players is going to stop their unconsciousness from disengaging.

What I mean by “clear rules” is that is that the compromises and concessions need to be properly telegraphed to the players. You do need to get some work done. For example, if you don’t want to make doors destructible despite the player holding a crowbar, make that door wood look really thick, and do display destruction decals when the door is hit.

2. Unless VR catches on, and the players will welcome shorter experiences and make them as commercially viable as movies. So far, while short linear action-adventures do make good money – yay! – they do not make the kind of money needed for a full devotion to the 5-Layers. And I cannot imagine the 5-Layers applied and be flawless in longer games like SOMA.

Of course, the 5-Layers is just one approach to the narrative design. I’m sure there can be others (see: Telltale). There have to be others, because, as I said, 5-Layers looks great on paper, but it’s too hard to execute properly in the real world.

I accept that game design might be harder than any other act of designing an escapist experience, but it should not be a hundred times harder.

But do not let my current obsession with cohesiveness of interaction cast a shadow on what I consider a milestone in gaming history. Do check out SOMA, and hopefully buy it. You truly do not want to miss out on one of the most important and mind blowing games of the last few years.