(This is an archived old post from the previous version of the page.)

It’s a relief that Alien: Isolations seems to be a commercial success, and gamers just love it. It has nearly three thousand reviews on Steam with staggering 94% of the users recommending the game. It got some lower scores from a couple of gaming websites, but it also enjoys 9/10s from respectable sources like PC Gamer.

Why is that a relief? Because it makes my critique of the game so much easier for me. Even though I always try to be clear that I analyze various games on this blog only to both learn and educate, it somehow always feels a bit weird to talk about the games of other developers. (EDIT: Luckily, I am not alone; here’s a much more insightful post on the game by Thomas Grip of Frictional Games).

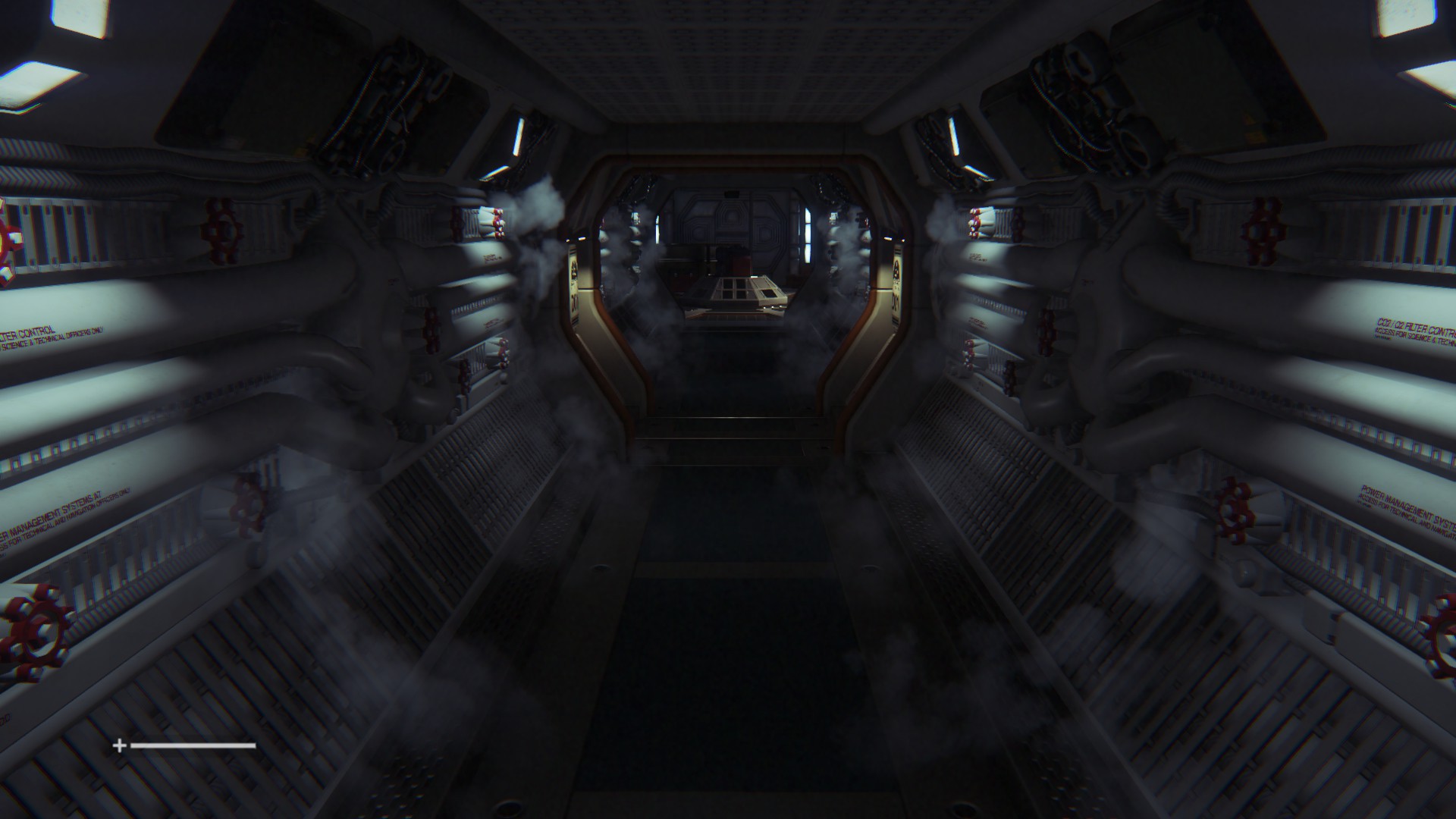

As you might suspect from that intro, I did not find the game engaging or immersive, and I will try to explain why. But, quickly, was there anything I liked? Yes, some of the visuals were ace…

…and the tension was incredible.

My favorite moment of the game was when I stopped hiding from the alien and moved through areas with the flamethrower, ready for an encounter. When I heard the alien appear, but didn’t see it, I panicked and just waved the flamethrower around, accidentally killing an innocent android.

Good times.

Unfortunately, for me even the tension was a problem, as there was simply too much of it, what resulted in a flat pacing. When everything is cranked up to eleven, I either become numb (vide: the latest Transformers movie) or I overload – but I am not properly engaged anymore. So the reason why I enjoyed the tension in the game was that after a few hours, after all the game mechanics were revealed and I experienced them enough, I used a cheat that allowed me to avoid 90% of the encounters with the creature, making the pacing more to my taste.

(Some people believe I have ruined the experience for myself this way: a) I just literally said I didn’t, b) please read this — Alien does have difficulty levels, and I have simply added one more myself).

There are more things to discuss but for now I want to focus on just the opening minutes. Be warned — there will be a lot of complaining here. However, if you read this post to the end, the conclusion might surprise you. Let’s go!

What do we do when we start a video game and are in control of the protagonist? We check out the controls, we prod and poke the world, we try to understand its rules.

In Alien: Isolation, we wake up in a room full of personal “memories”. See those two photographs there, at the top of the bed?

There are also other interesting items like a magazine and a book.

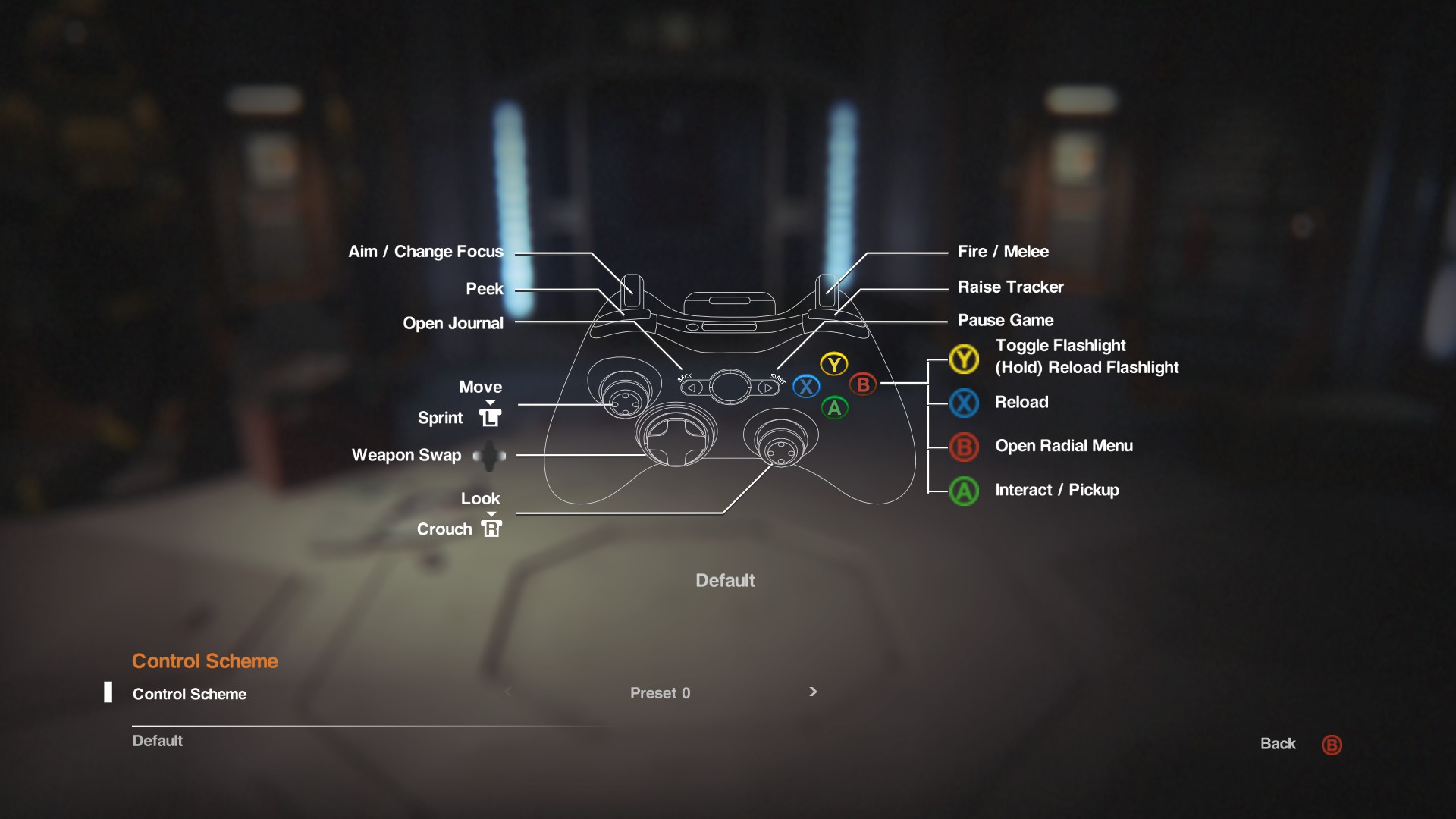

The problem is: you cannot take a good look at any of these items. There is no zoom button. The world of the game invites you to investigate it, but the game denies the option to do it right. It’s not an unsolvable problem. One could use the solution of Bioshock(s), or…

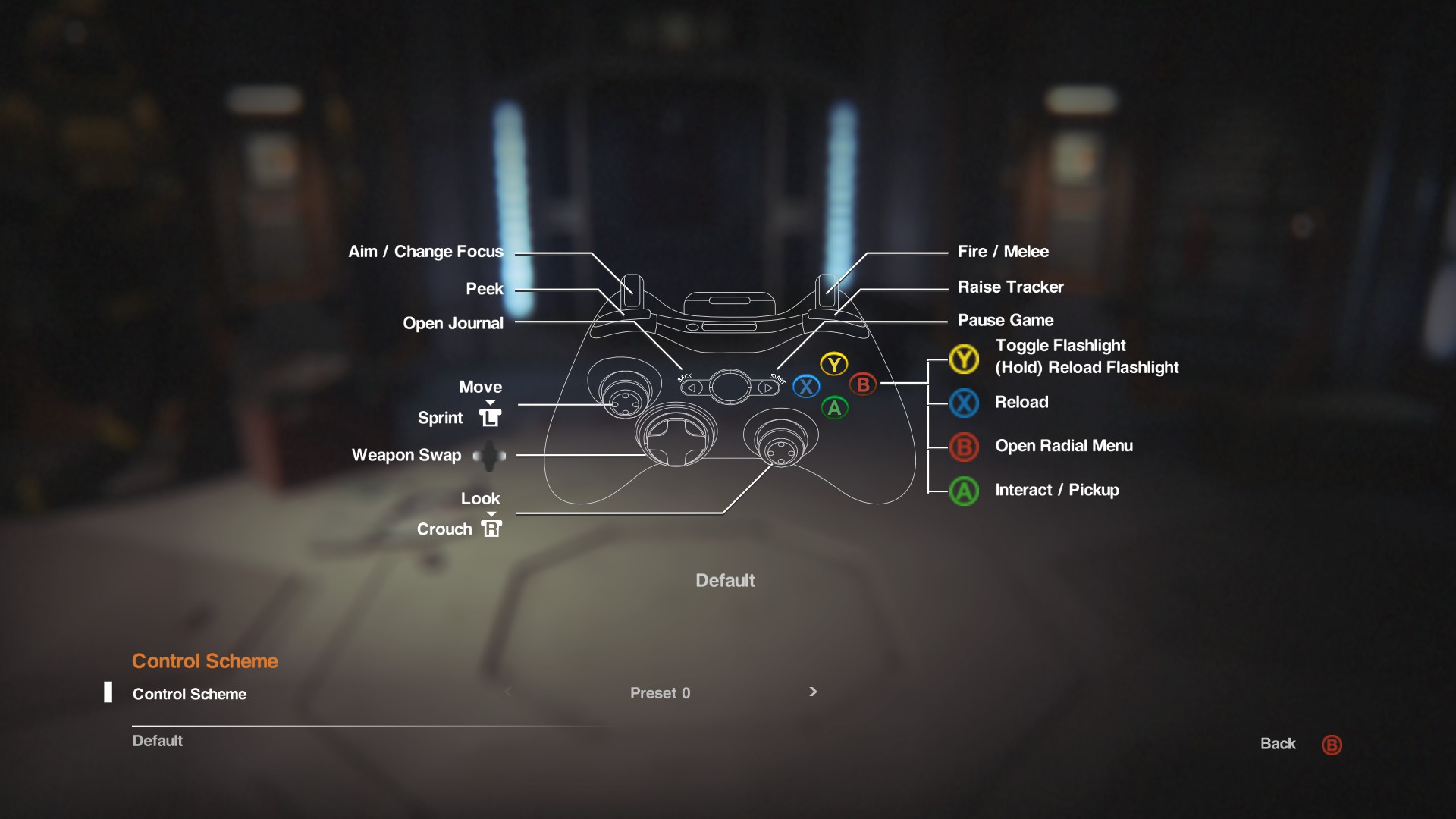

…move Flashlight to D-Pad Up, move Crouch to (B) like in 99% of other games, and this way free the Right Analog Stick for a zoom (solution used in many games).

The effort here is admirable: instantly humanize the spaceship by filling the space with personal items. But that’s why it feels wrong when I, the player, cannot fully connect to the idea, feeling that the game itself is in the way.

But wait, it all sounds like an extremely small problem, right? So you cannot zoom in on photos, big deal.

Let me explain why for some people (like me) the problem is actually bigger than it may appear. I find the PENS model very useful for game design analysis, and, in short, that model assumes that a game needs to make sure it has something to offer in the following three areas:

– Autonomy

– Competence

– Relatedness

Note how all three are hurt by such a simple thing as a lack of zoom (or by bringing the player’s attention to the lack of zoom). Autonomy: because the player had a very reasonable idea but could not execute it. Competence: because the player does not know how to solve the problem, and tries to crouch, squeeze between objects to get close to the photos, etc. – without any real result. Relatedness: because a glimpse of human connection is within reach, only to be denied.

Speaking of controls, one other thing, one that’s hard to justify, is that you cannot run in this first chapter of the game. Why? Absolutely no idea. Possibly the reason was not to overwhelm the player with the control scheme. But you cannot run accidentally in the game, and the creators did not need to telegraph the run’s existence at this stage of the game. This way or another, when I checked the control scheme and saw “depress LS to run” I was disappointed when it then turned out that the activity was disabled.

But here is something that killed the agency for me. The first thing you see in the game is a terminal…

…and after you check it out, this happens:

To me, the whole trick to proper immersion is to make the player/reader/viewer forget they are experiencing something that has “already happened”. The book is written, the movie is filmed, the game is done – and yet we want people to experience our creations as if they are happening live, right here, right now. Even if it’s a WW2 movie or a sci-fi game.

When you play a story-driven game like Alien: Isolation, you should feel like you are creating a story yourself. The events, the NPC deaths, even the ending cut-scene – all of these things already exist, they’re on your hard drive, waiting patiently to be triggered at appropriate moments. But you don’t want to know that. You want to feel like whatever happens in the game, happens because of you, dynamically, live.

So when I see an authoritarian objective like “Get dressed” all of that is taken away from me. This is a “perfect” reminder that I am nothing more but a puppet. My autonomy is killed, my role in the game gets limited to scratching things off a checklist I don’t even understand.

Zooming in:

[ ] Get dressed

[x] Speak to Taylor

[ ] Speak to Samuels

Why?

Why do I have to talk to Taylor or Samuels? And who are Taylor and Samuels?

And of course a certain gate in the game will be unexplainably closed until you do all of the above. A magical trigger will open it up after you’re done with your fedexing, and you can continue the adventure.

Also, the spots in which I can complete a task are circled on the ship’s map. Even if I have never been to a place before and I should not know that the objective could be achieved in that particular spot (i.e. a case where the game loudly announces it knows more than the player).

Is Autonomy hurt? It is. I have nearly zero autonomy. I am clearly told what I have to do and where to do it. I can execute the tasks in the order of my own, but that’s it. I’m playing fetch, without any illusion of writing my own story.

Is Competence hurt? Sure. The game does not even trust me that I want to play it. Proof:

How to fix this?

(BTW, I consider mission objectives as crutches to a questionable design. But that’s a separate, big topic, so let’s assume for a second that we do want mission objectives in our game.)

Just, simply, justify those objectives. For example, you could cheaply and easily justify “Get dressed” and “Speak to Samuels” at the same time. Have Samuels greet us when we wake up. “Finally, Ripley, you’re awake. Good. Get dressed and come see me. Something happened.” Voila, display “Get dressed” and “Speak to Taylor”.

When the mission objective is just an echo of what the narrative “told” the player, it’s okay. But when the mission objective is or is ahead of the narrative, both Autonomy and Competence suffer, negatively affecting immersion and engagement.

So I am fifty seconds into the game, and my initial trust and bias (“I paid for the game therefore it must be good”) are quite crippled. The next thing I do is I approach this unknown object and see the option to use it:

When I use it, the glass bed covers go down, and when I use it again, they go up. Not only this is such a random thing — why can I interact with this but cannot interact with a hundred other things in the game like this one?..

— but it also causes a dissonance between the heroine and me. She knows the purpose of the object, but I, the player, don’t. So whatever the object does, it’s surprising to me, and it shouldn’t if we wanted to keep the player and the character we play as in sync. This not only hurts Competence, but also Relatedness.

All of that in sixty seconds. I didn’t even leave the starting room yet.

And that’s just the beginning of the long list of problems I had with the game.

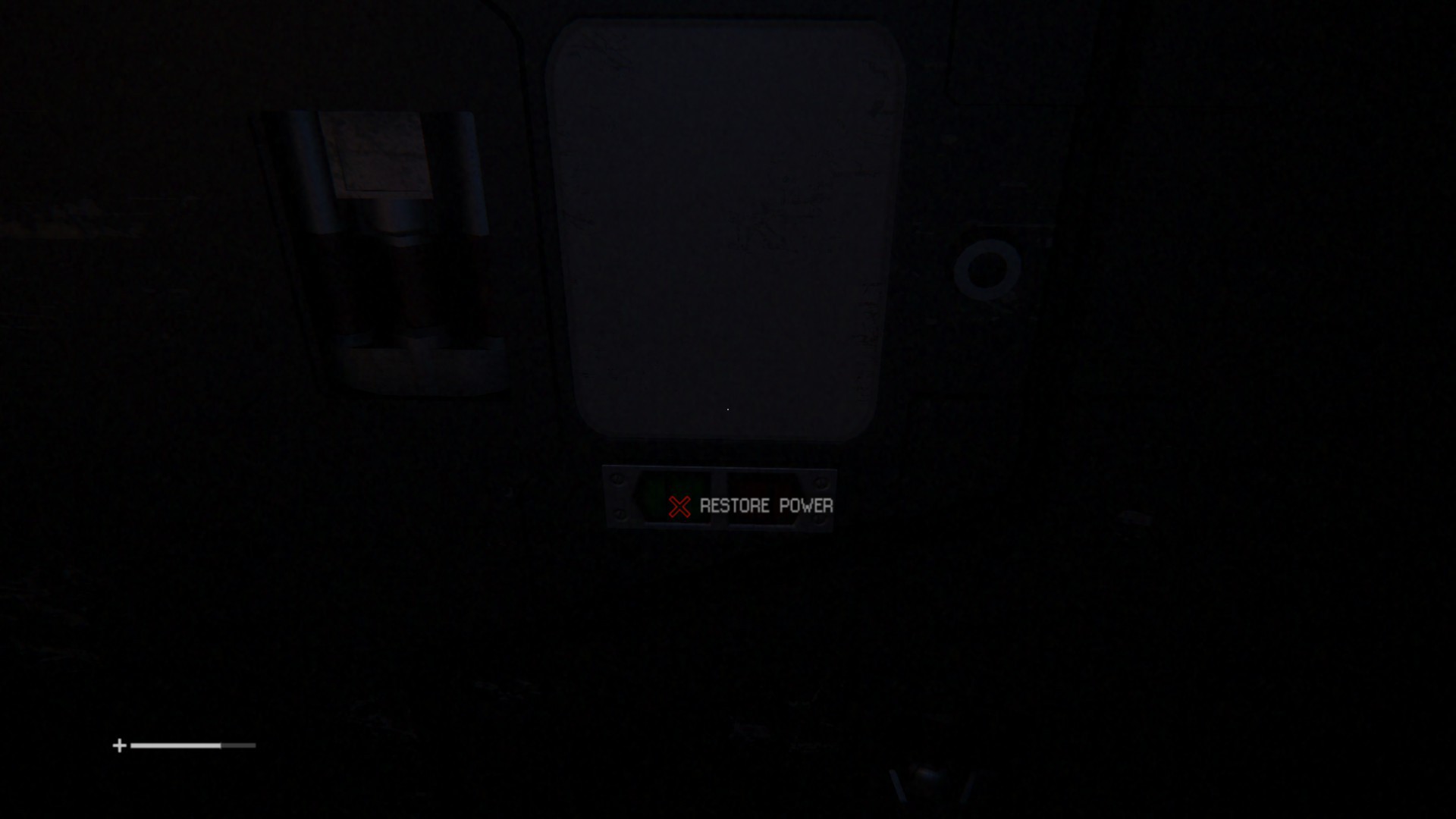

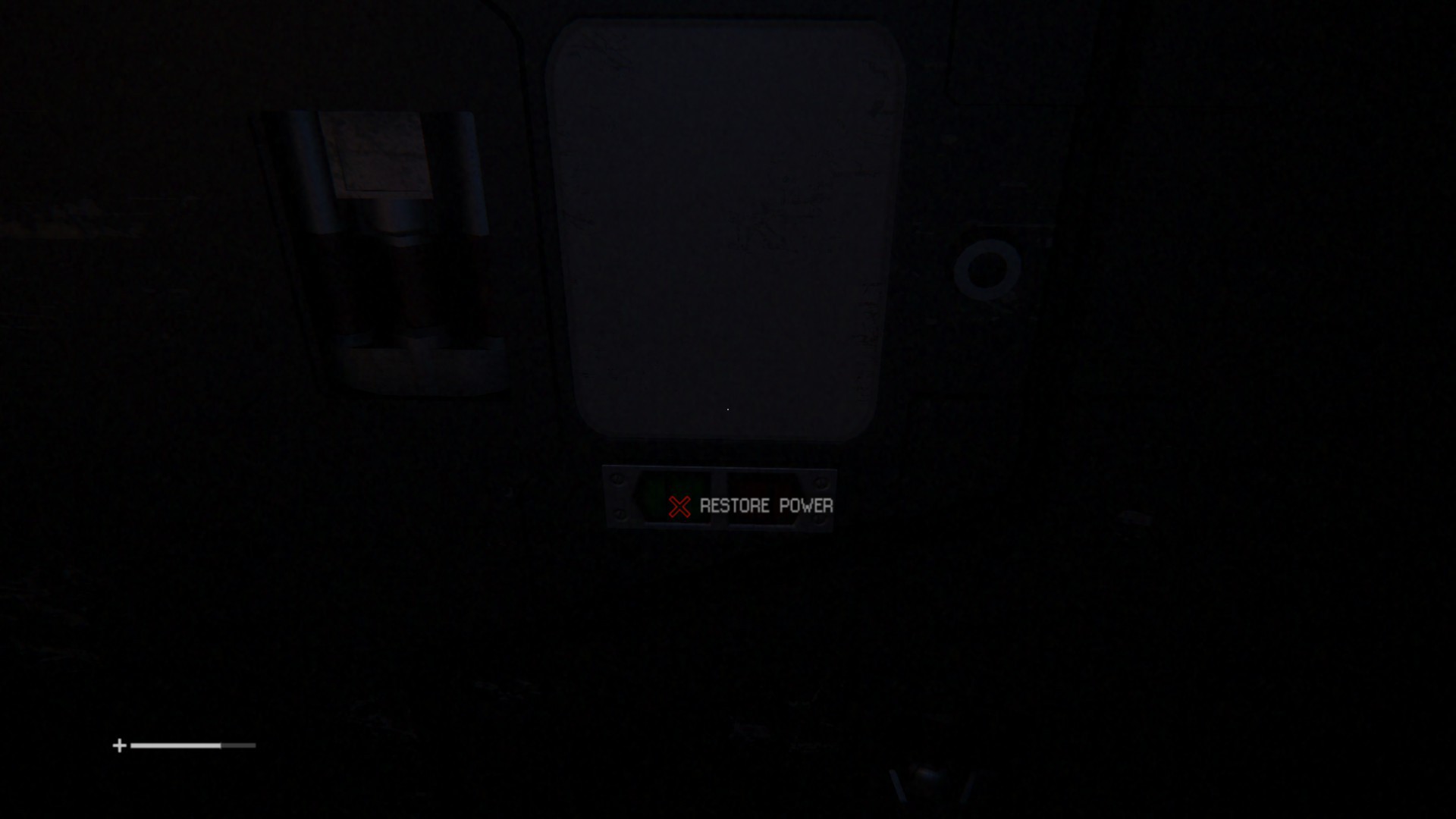

I did not expect its core design to be 99% about gate-based content denial. Sometimes to open the door you need to restore the power.

Sometimes you need a plasma torch.

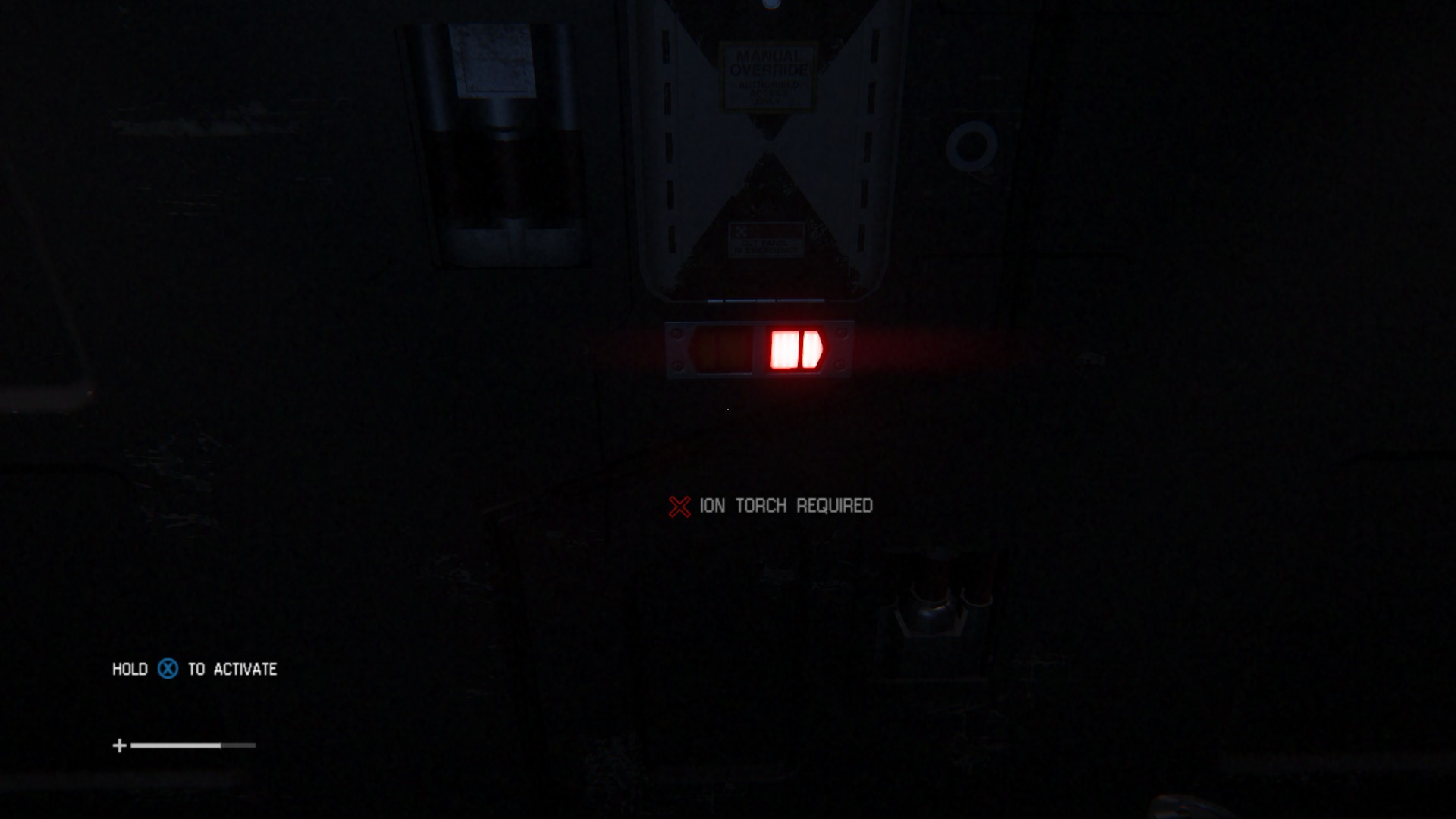

Or an ion torch.

Or a maintenance jack.

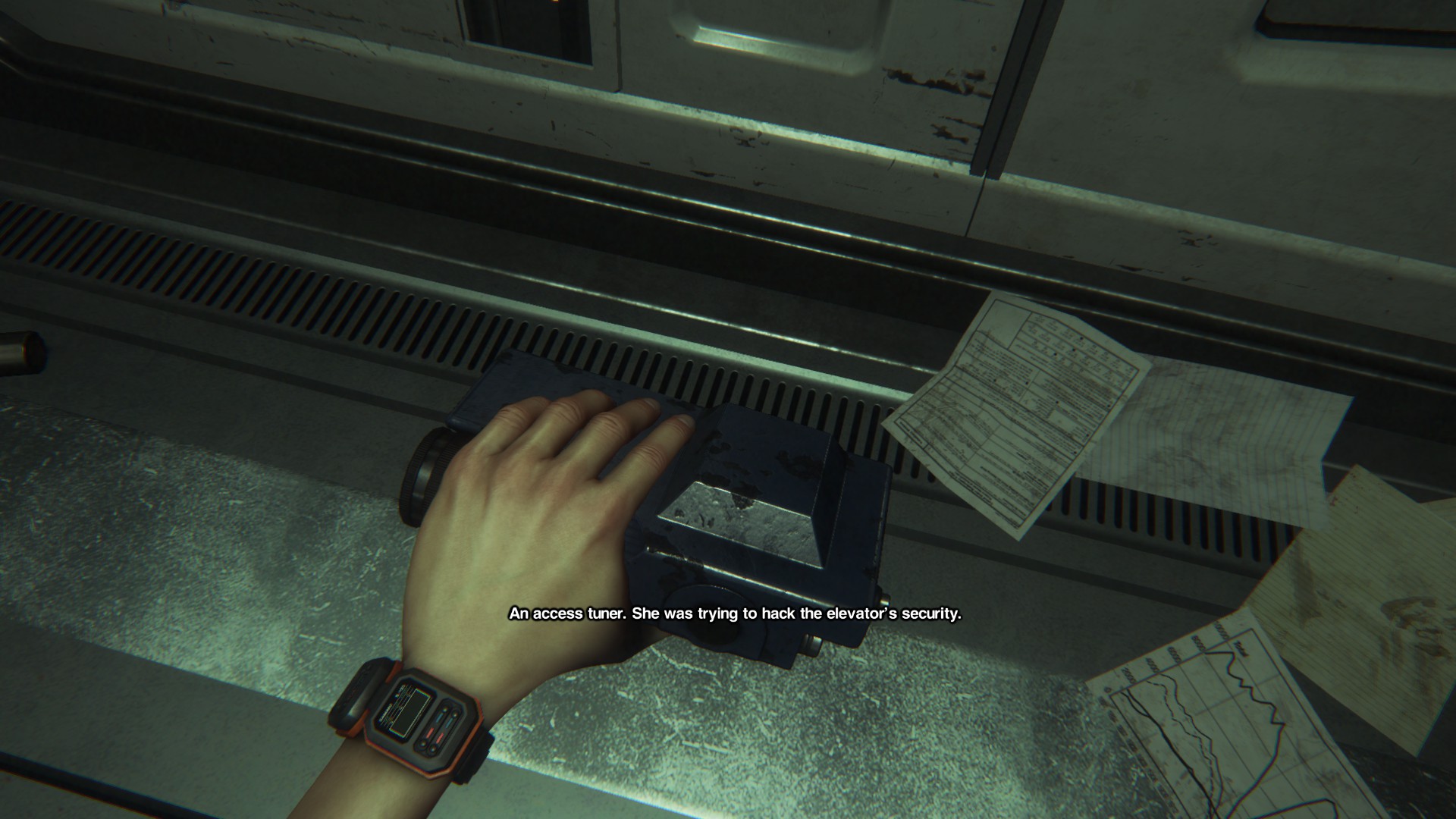

Or security access tuner.

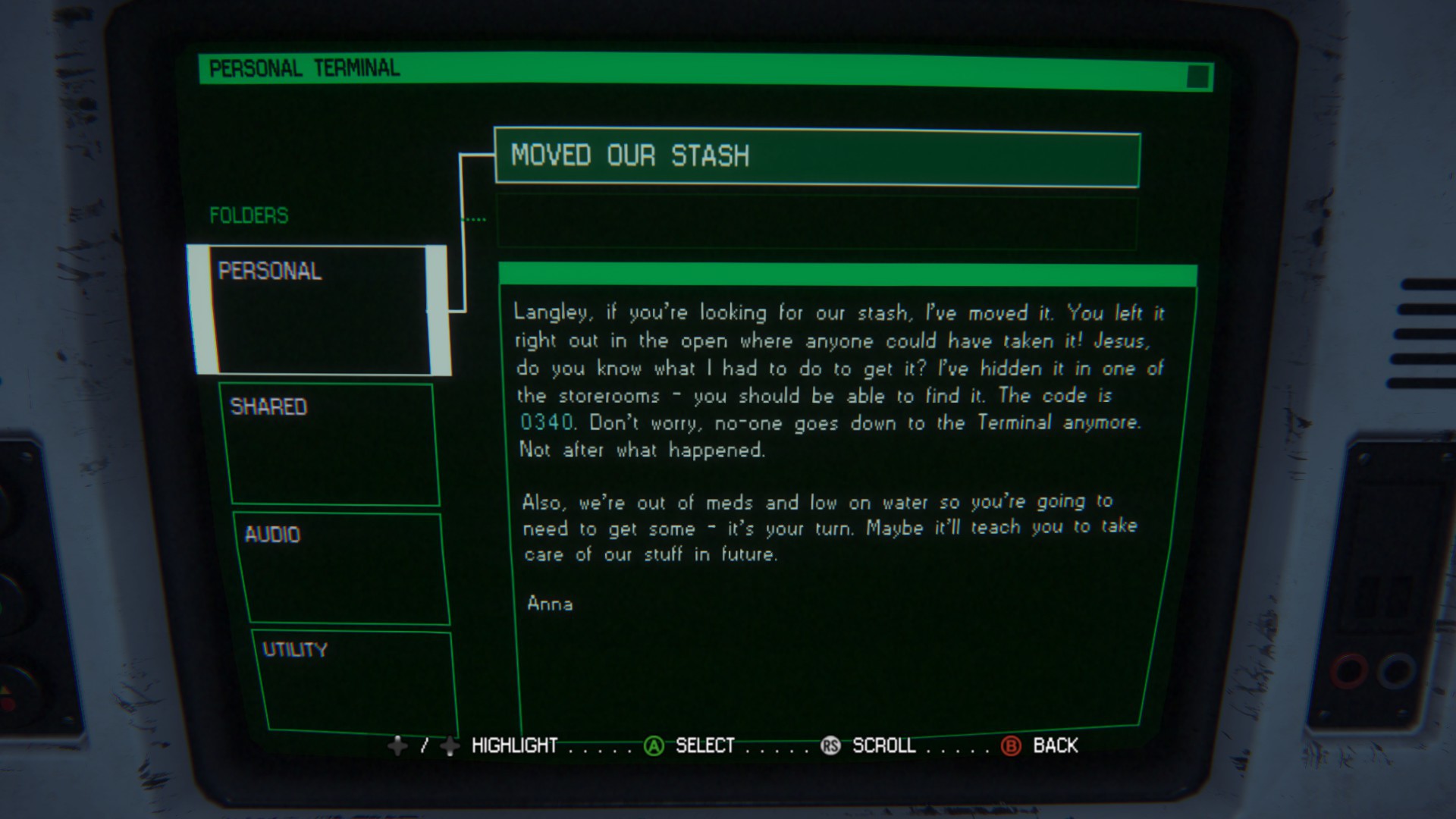

Or a passcode.

Or a keycard.

Sometimes there’s nothing you can do.

Sometimes there’s really nothing you can do.

The story the game tells is as boring as the personal notes you read on various terminals (why are these notes available to us?)…

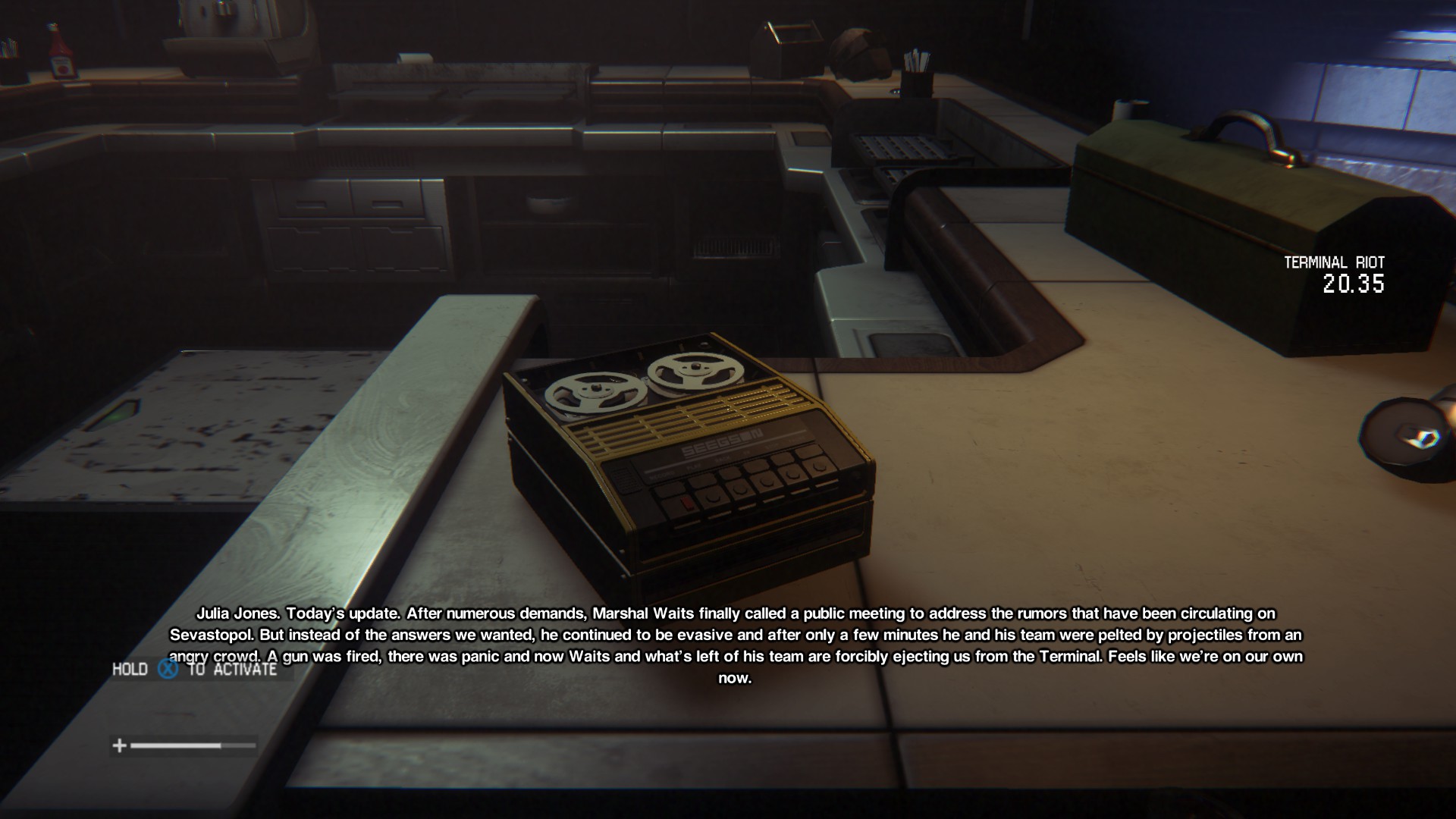

…or found in these gigantic tape recorders (why is audio digital in the terminals and still so Bioshock Infinite elsewhere?).

The heroine is, to me, the least interesting, bland protagonist I’ve seen in a long time (YMMV, apparently). All of the tired design clichés are present, too, including the heroine’s inability to pass over a suitcase…

…heavy handed exposition…

…graffiti no one would ever paint…

…and questionable scripting. Like, you cannot open the elevator door yourself, this guy has to do it, apparently pressing a button requires special powers…

…only to literally five seconds later hear from him that you have to press the floor button yourself.

Finally, my personal favorite. You kill a guy with a wrench, and yes, finally, a gun! But no, you cannot pick it up. You can search the guy and take all of his belongings…

…but not the gun. Look, it’s right here. Right. Here.

But no. And the reason is that a bit later in the game you find the gun during a scripted sequence.

Look. Honestly, all of the above is a design 101. There’s just no way that the creators of the game do not know of these problems. My suspicion is that the game went through a couple of redesigns and a period of artificially extending its length. Because of the demands of the “AAA” world. Hence the wonders like the unpickable gun or the overload of closed doors. (Note: however these extenders bother me, I do think that commercially they were the right thing to do!)

A bit earlier I said that despite my lack of enthusiasm for the game, “the conclusion might surprise you”.

Let me quote the opening paragraph again:

[…] Alien: Isolations seems to be a commercial success, and gamers just love it. It has nearly three thousand reviews on Steam with staggering 94% of the users recommending the game. It got some lower scores from a couple of gaming websites, but it also enjoys 9/10s from respectable sources like PC Gamer.

To me that such a great reception is infinitely more interesting than pointing out this or that design error. No, wait, but that’s exactly the thing here — are they really errors at all?

These are not some carefully selected tweets, I just typed in “alien isolation” in Twitter search and voila, took the first two.

What is happening here? To me personally, Alien: Isolations is a tired, derivative game. But I am clearly in the minority here! A lot of people genuinely love it!

I am very interested in finding out why. Because maybe I am hipstering around here, “nitpicking”, and don’t see what people really look for in a video game.

So far I could come up only with the following answers:

1. All that a lot of people look for in a video game is “something to do, preferably with clearly established goals”. As long as it’s decent and in a cool world, it’s fine. This would explain the success of games like Alien or Assassin’s Creed or any other shopping list/fedex quests kind of games. You buy such a game, then do stuff in it for weeks, especially if you play in 1-3 hour doses.

2. People don’t have enough comparison material. We still live in times, when even the most respectable magazines can give a game 9/10 “despite the story being bad and boring”. Red Dead Redemption or The Last of Us raised the bar only temporarily, and we don’t get such quality games often enough for the bar to stay high permanently (I am talking AAA here, as the influence of indies – including Telltale – on the mass market is not as substantial).

3. The power of video games is so strong that, in the case of Alien: Isolation, the atmosphere or the thrill of the alien hunting the player overshadows everything else, and is the reason enough to love the game nearly unconditionally. (side note: a fellow developer described it this way: “IMO it’s the magic circle. People don’t just suspend disbelief, they also suspend real life mental models. They enter the magic circle looking for scares [with] no metal models of expected experience = profit, regardless of incoherence.”)

Which one is true? I have no idea. Maybe all three, maybe none, and I am sure more explanations are possible. But I genuinely want to know. We are not making games for ourselves, but for the public who pays for them with their hard earned money, so understanding why some theoretically badly designed games find a large audience seems to be crucial to the craft.

P.S. I think I got my answer. Number 2 on the list just happened to me personally with The Evil Within. At this very moment I think that #2 and #3 are the valid answers, combined with the state of mind one has when approaching the game (I assume if I did not have an extremely high expectations of Alien: Isolation, I would be able to enjoy the game more).