(This is an archived old post from the previous version of the page.)

Do you know how people who want to harshly criticize something usually begin with a few words that are supposed to soften the blow? Yeah, I’m going to do the same thing here.

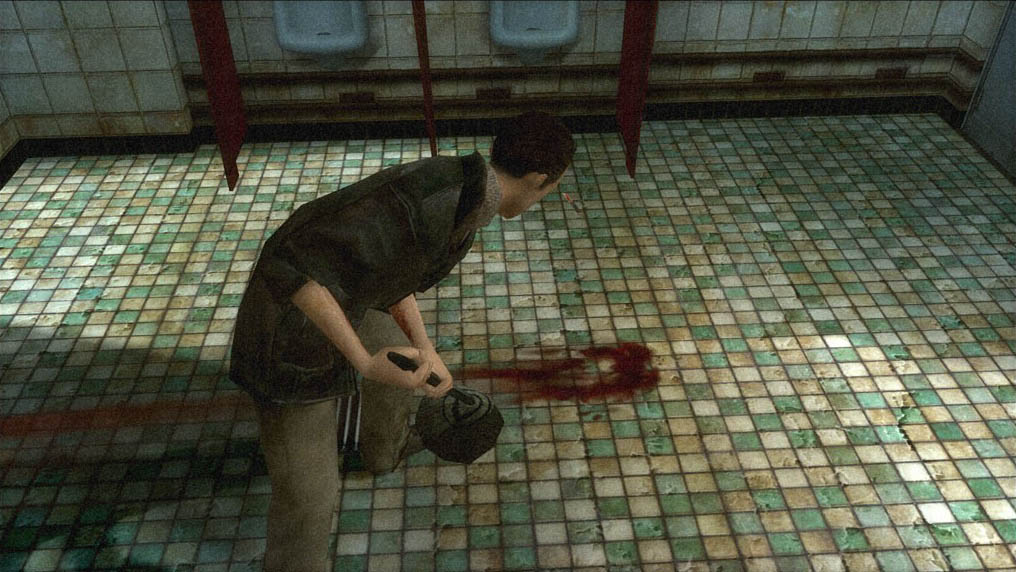

Fahrenheit – aka Indigo Prophecy – was a revolutionary game. I don’t use the word “revolutionary” lightly. Yes, Fahrenheit suffered in the last third, mainly because of the publisher’s ultimatum to deliver the game “right here, right now”, but still, the opening sequence shall forever be known as one of the best and most influential first hours in the history of gaming.

Also, Heavy Rain was good. The “Press X to Jason” fragment annoyed me, but I enjoyed everything else, even the unfair twist. I’m happy that the game ultimately sold quite well, and I’m happy that a lot of people agreed that interactive dramas are a valid proposal.

But – and now it’s time for the blow – Beyond: Two Souls is a step in the wrong direction. It’s an phenomenal game for any designer studying the art of narrative in games, but it’s a bad game otherwise. Although, as it is not a consistently bad game, “it’s a mess” would probably be a better description.

To be perfectly honest, there are people out there – including one of the co-owners of The Astronauts – who genuinely liked the whole thing. I’m not quite sure how that’s possible, but they did. Good for them! But for me, it’s a nearly perfect example of how not to make an interactive drama. The only things stopping it from being “perfect” are terrific action sequences, some production values and the fact that despite the creator’s best efforts, I still managed to enjoy and be thoroughly impressed with a couple of chapters, especially those in the second half of the game. Heck, I even almost shed a tear.

But why exactly am I calling the game “a mess”? In the spirit of a few earlier installments of this unofficial series of blog posts, I want to focus on the opening five minutes only – but it should be enough to show where the core problem resides.

Well, okay, if I focused on just these five minutes, it’d be a mighty short blog post, as the game opens up with a very, very long cinematic. So let’s pretend that did not happen and assume the game begins with a playable flashback sequence in which our heroine, Jodie, is eight years old, lives in a military complex, and some people run experiments on her.

I will be describing that sequence in fair detail, but I don’t consider it a spoiler. There are no real twists in that sequence, and there are no revelations or surprises unless you have no idea what Beyond is about.

So let’s talk about the major sin of the opening – and, actually, most of the game – which is…

No, it’s not the fact that the game is an interactive drama with a minimal amount of “true” gameplay. We cannot have that conversation after the greatness that was The Walking Dead, which is 95% cut-scenes.

No, it’s not the linearity of it all. We cannot have that conversation after the greatness that was To the Moon, one of the most linear story-telling games in history.

The real culprit is, then: the lack of Player-Protagonist Sync.

Yeah, it’s a term as graceful as “Ludonarrative Dissonance”, but bear with me for a second here. Also, please remember that everything I come with in my blog posts is merely my opinion and my point of view. I don’t claim to be 100% right. These blog posts are meant to inspire further discussion and research, not to “inform”. Anyway, moving on…

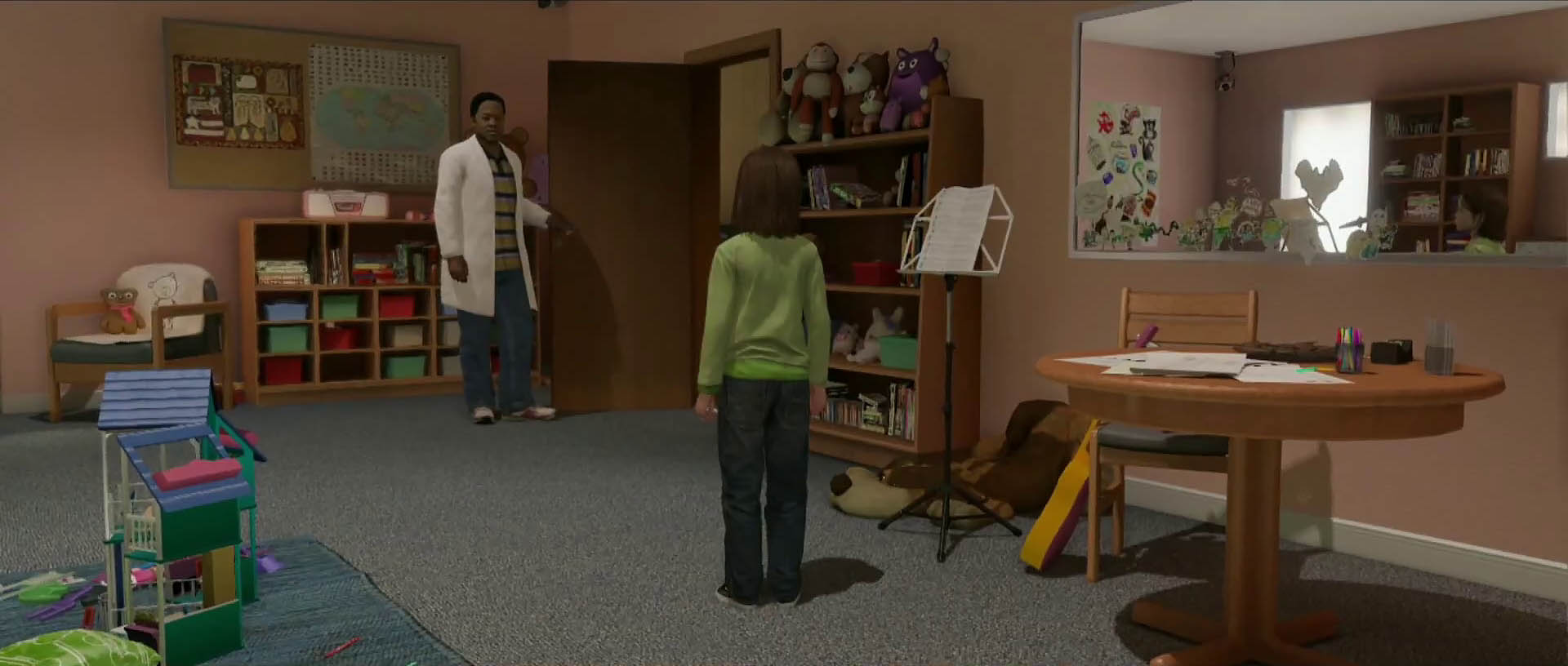

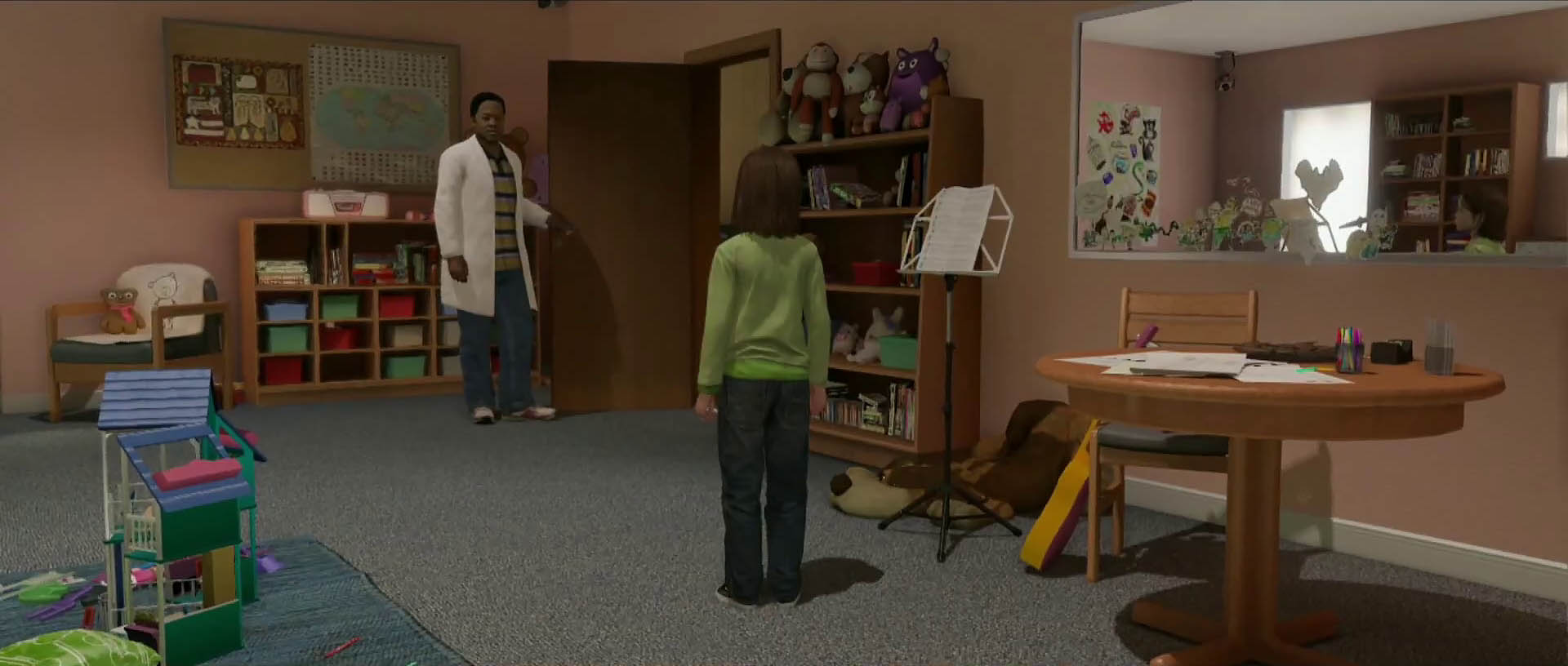

The surprising thing is that, on the surface, the opening minutes of Beyond are perfect. Here is what happens. You are a little girl with supernatural powers, and you live – but what a sad life that is – in a room somewhere in a military complex. A man comes in and says it’s time for yet another experiment. He goes back to the door and waits for you there.

You can listen to the man and just go, or you can pick up a toy and play with it, you can watch a cartoon on TV, you can lay on the bed. When you do that, when you try to delay the inevitable, the man by the door reminds you that “it’s time” and “we need to go”.

Now, this is the opening of a video game, the time when the players love to poke things, check out the controls, admire the environment, and generally mess around.

So, because the players are like children when they start a game, and the players are also literally a little girl in a room full of toys and things to do, this “messing around” is nicely written into the narrative.

Also, you are about to be a subject of an experiment, and this does not sound pleasant. So everything you do is in the room delays that unpleasantness. Which is exactly what Jodie, our scared little eight years old heroine, would do.

So, a perfect sync between the heroine and the player?

No.

Story-telling games have a story to tell. That means the story exists even before you launch the game. Even if the story has multiple paths to choose from, it is already written and implemented before you even press Start. The designers know darned well how it all ends, they know all of your options, the pre-rendered ending cinematics are waiting in the game’s folder on your hard drive.

The art, the magic trick of the design of story-telling games is in making you believe it’s “all you”.

One of the ways to achieve that is Player-Protagonist Sync. It comes into existence when the players are able to project their personality onto the hero or heroine of a game.

There are four basic rules to make this happen, and Beyond breaks all four.

Side note: not necessarily all four rules are broken for all players, e.g. some players might enjoy being evil, and in such case there will be a proper sync between the authoritarian narrative (“be evil”) and the player’s mind (“I want to be evil”). But in that case other rules get broken anyway, as the game actually does not want the player to enjoy being evil. Yeah, it’s a mess.

First, at the starting point the protagonist in the game needs to be someone whom the players would like to be for a while – consciously or subconsciously – in a holodeck fantasy: a daring archeologist, a private detective, a heroic soldier, a gangster with a gun. It’s not limited to “cool characters”, however. You may want to be a simple man fighting for love or a hard working single parent. But the character needs to be someone we can quickly connect with. EDIT NOTE: Please see my post on NeoGAF for more info on this “rule”.

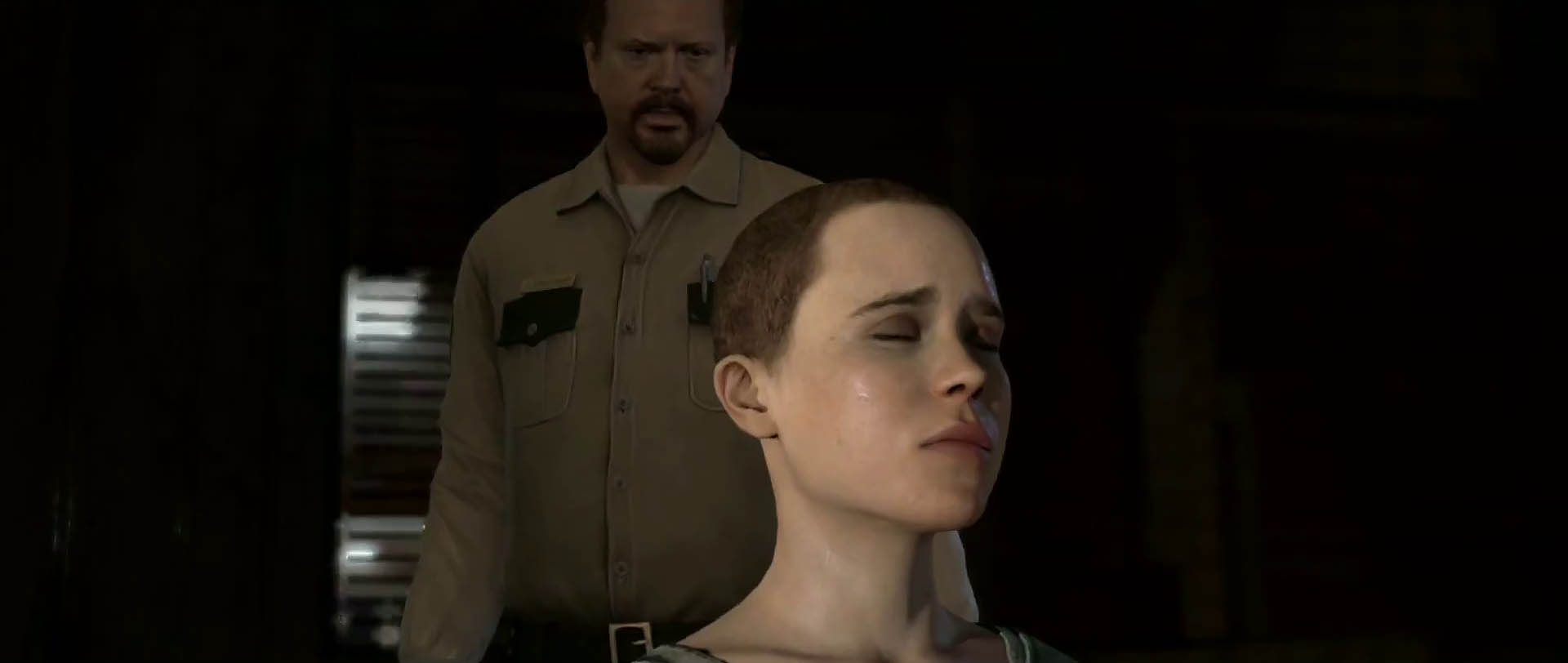

How does Beyond break this rule? The opening cut-scene shows that the adult Jodie’s life is shit and full of suffering, and then the opening gameplay shows that the young Jodie’s life is shit and full of suffering. We know, then, that recreating Jodie’s life until that opening cut-scene is going to be nothing but pain and misery. Not exactly something we can easily and quickly slip into, as much as we try to convince ourselves that we’re open to “serious, deep themes and experiences”.

The game would immensely benefit from removing the “adult Jodie’s a wreck” intro cut-scene, or if the playable “scientists experiment on young Jodie” flashback was put later in the game, after the opening cut-scene was followed by a few a bit more “pleasant” segments. In other words, show me how I am doomed in the future, but follow that with something nice, or start with something nice and then take me to hell. But don’t offer me a few hours of an agonizing journey from bad to worse. Combined, both sequences – the opening cut-scene and the opening playable flashback – make it devilishly hard for the player to invest mentally in the protagonist. Instead of wanting to be Jodie, we distance ourselves from her, and this obviously does not work in the experience’s favor.

Second, to avoid losing immersion, the game cannot force the player to execute (in gameplay) or observe (in cut-scenes) actions that are against reason or player’s moral system. This is why it is so annoying in Max Payne 3 when this alleged professional enters a house and gets knocked down from behind like an amateur, and this is one of the reasons why we cringe when we are forced to torture a guy in Grand Theft Auto V.

How does Beyond break this rule? I will describe it in detail a bit later, but in short, the game expects the player to screw around and give the medium – a lady who is a part of the experiment – a heart attack. We cannot refuse to do it, even though we fully understand how our actions negatively affect her. All we can do in the game is to keep hurting her.

Third, the game cannot put the players into situations that loudly remind them of the game’s limits. This is yet another reason why the torture scene in Grand Theft Auto V sucks: we desperately want to have a say in the matter, “in real life” we would like to consider other options. But we cannot do that, the game has a certain story to tell. It’s not a problem in itself, but when such fragment of the story is in direct conflict with the player’s moral system, the immersion gets broken.

Note that this has nothing to do with the fact we are playing as a flesh and blood, established character who “would behave this way”. Hint? Note the “we are playing” part. When we role play someone in a video game that has a specific story to tell, we can only stay immersed in the narrative if the protagonist’s actions are not in deep de-sync with the player’s own mental processes.

How does Beyond break this rule? It’s not even about corridors we can walk into only to be automatically turned around halfway through. It’s about putting a little girl into an unpleasant situation, one that we cannot fight it in any way. Our only option is to go along with the narrative. If the player’s actions were neutral or good, this could work, but by forcing the players to act in the way they clearly do not want to, the game reminds us we are merely actors reading out loud the script that’s already been written. We always are, but game design is like magic tricks: it is about hiding the truth, not about exposing it.

Things are even worse than you think, actually. Let me use another example from the opening.

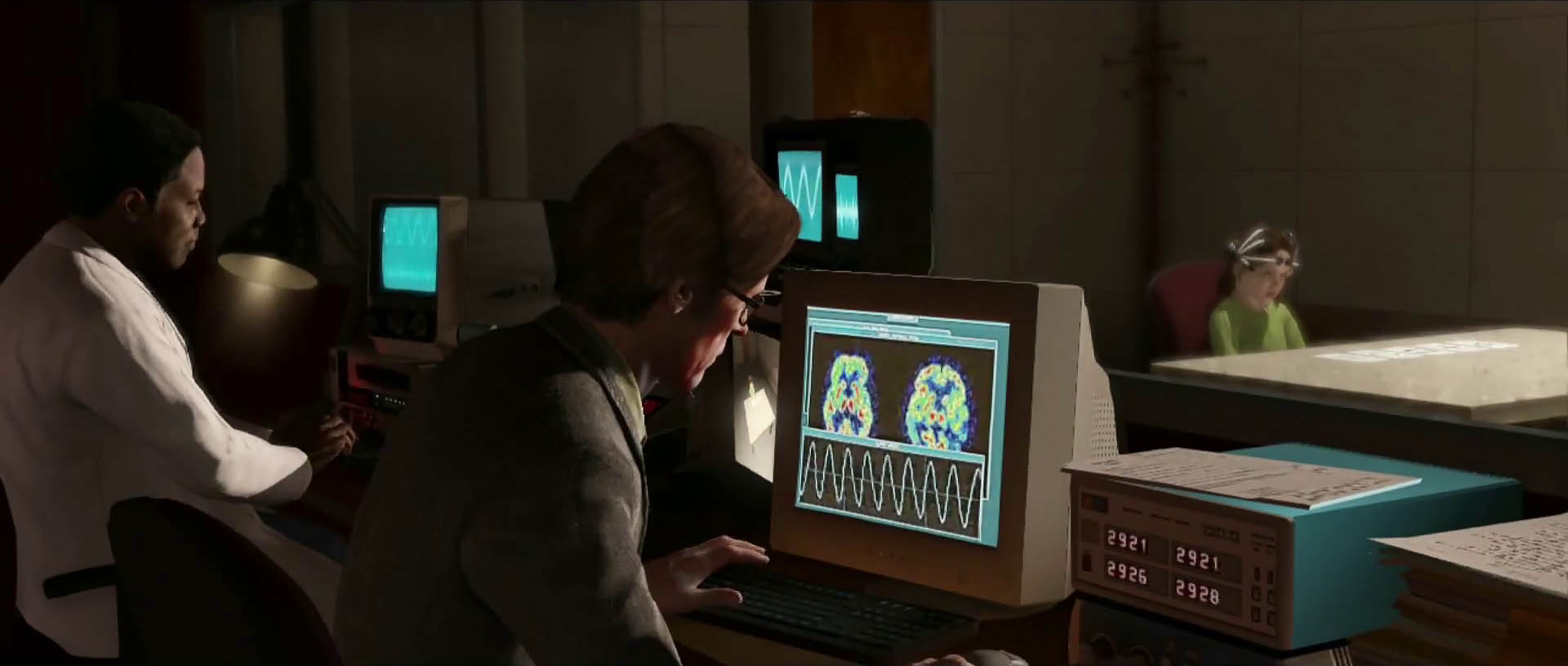

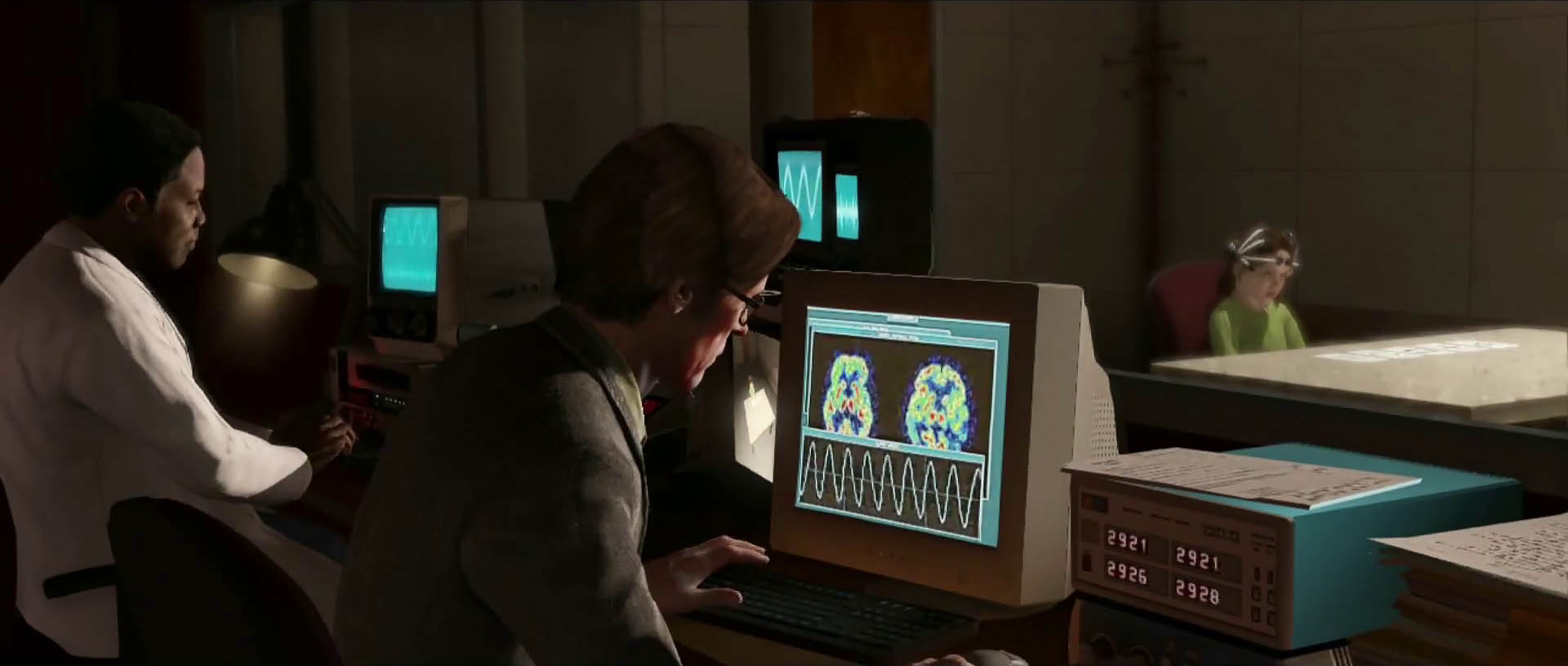

The way the experiment works is that two charming scientists ask Jodie to interact with the medium who is in another room. We do it by switching from Jodie to an entity called Aiden, a “ghost” that’s attached to her. The ghost can, for example, go through walls, and push objects around.

The scientists ask us to move an item in the room where the medium is. We do that, and it scares the medium a little. “One more” – says one of the scientists. We have no option but to go along with the request, so we move another item. The medium is clearly scared.

I want to role-play a nice entity, so this is where I stop. I am not asked to move any more items around, and since I want to avoid scaring the medium to death, I switch back to Jodie. However, nothing happens when I do that. The medium is silent, the scientists are silent, Jodie is silent. The game clearly wants me to do something, and it is not hard to figure out it is to keep terrorizing the medium. But I keep on doing nothing. After thirty seconds, Jodie says: “Come on, Aiden, help me out here…” – even though the scientists stopped asking me to push any more objects around – and I know the story will not move on until I switch back to the ghost.

I do just that, and I attack just one more item. As expected, the medium gets even more scared. “I’ve had enough” – says the medium and goes for the door.

I am not a monster, so I stop again and switch back to Jodie. She’s just sitting there, looking a little bored. This lasts for ten, fifteen seconds, and then a cut-scene kicks in. In that cut-scene, both scientists storm into the room, panicking, screaming. Jodie is shell-shocked, tears flowing down her cheeks, blood coming out of her nose.

Wait, what? How did it go from “bored Jodie and scientists” to “end of the world”?

Well, again, it does not take a genius to realize that I “misbehaved”. Apparently, I was expected to keep messing around as the ghost, break all items in the room, terrorize the medium, and possibly even take control over one of the scientists. This was supposed to sell me Aiden as an uncontrollable, possibly malevolent entity, and show me what Jodie has to live with all her life.

But it was me controlling Aiden, and I am not a psycho. Not only I had no desire to scare people to death, the game actually kind of allowed me to do that. Only to then show me a cut-scene that not only rendered all of my role-playing useless, but one that also exposed the fact I am merely the designer’s errand boy, and not someone shaping his own fate in a virtual world – even if in most games that shaping is nothing but an illusion.

Fourth, player actions need to have interesting outcomes. We love the choices in The Walking Dead because they always lead to emotional change.

How does Beyond break this rule? A few good times we know quite well what’s going to happen before it happens. Stan Lee once said that surprises are the key to proper narrative: if the reader knows what’s going to happen, and five minutes later it happens, then this is when we lose the reader.

When we begin Beyond, we have a pretty strong suspicion of what’s going to happen: the girl will have to go with the man, then they will get to some kind of lab, then there will be some kind of experiment, then something will surely go wrong, etc. And exactly these things happen. Compare the opening of Beyond to the opening of The Wolf Among Us – another interactive drama released around the same time – and you will see the clear difference, and the nuclear superiority of the Talltale’s game in that department.

To sum it up, Beyond does not handle Player-Protagonist Sync very well, at least not in the beginning. We play as someone we subconsciously do not want to play as, the narrative forces us to do things we do not want to do, we are consciously recreating the script instead of getting lost in it and experiencing it as our own, and it’s all quite bland and predictable.

Later – much, much later in the game – when Beyond manages to achieve the sync for a little while, the game shines and even takes your breath away for a few good minutes, but then it’s too little, too late.

Of course, Beyond is not the only game suffering from this problem. Spec Ops: The Line, in which the designers awkwardly strong arm the player into being a mass murderer is another clear example – but there are many, many more.

Contrary to what some people say, there is nothing wrong with a game designer wanting to tell a specific story through a video game, nothing wrong with wanting to take the player on a specific journey. Just like there’s nothing wrong with pen and paper RPGs and game masters taking the party through a specific adventure that they prepared for them. It’s already been proven that if done right, if the Player-Protagonist Sync is achieved, story-focused video games can offer experiences that other medium cannot match.

Without the proper Player-Protagonist Sync, however, game designers are like a magician with cards falling out of his sleeves and rabbits jumping out of the cabinet below the hat.

But… Games that put the story-experiencing first are fairly new, and it’s not that surprising that some of them fail at achieving immersion – we’re all still learning how to properly merge story and gameplay into one cohesive narrative experience. So while Beyond is a disappointment to me (YMMV), I have no doubt that I’ll be the first in line for whatever next is coming up from Quantic Dream. Here’s hoping!